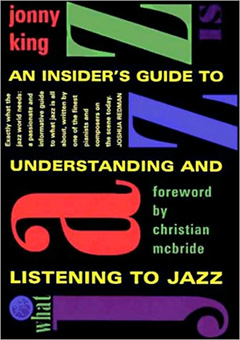

A Book by Jonny King

Years ago I returned to my college dorm room, nearly comatose from another insufferable Renaissance history class. I put on Relaxin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet, dropped the needle on “I Could Write A Book,” and lay down on our secondhand sofa. Red Garland’s eight-bar intro, Miles’s muted statement of the melody, John Coltrane’s roaring solo–I was instantly transported away from lectures, exams, and crummy furniture, and my head was bobbing with the pulse of Paul Chambers’s bass beat. Something about that record has always rescued me, no matter where or from what.

My roommate barged into the room midway through Red’s solo, and I opened my eyes. He grabbed his baseball cap and said to me, “So, is this number three or number four?” I shook my head, not understanding. Mark, knowing full well that I spent roughly half my nights playing piano in local jazz clubs, continued, “You know, isn’t jazz just, like, five or six songs that you guys play over and over? This sounds like number three or maybe four.” He smirked as he left the room.

Flustered and annoyed, I reverently put on John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, side two, first cut, “Pursuance,” and turned up the volume. This whole record is a monument to Coltrane’s spiritual rebirth and rediscovery, and I doubt there is a more passionate, intense exploration of musical possibilities in recorded music. Elvin Jones begins with a thunderous, rumbling drum solo, then Trane, McCoy Tyner, and Jimmy Garrison charge in with the melody. McCoy is off and running over the entire range of the piano keyboard, and my heart starts to race. . . .

I was jarred out of my reverie when Andrew from across the hall charged into the room. “What the hell is going on in here? It sounds like someone’s strangling a chicken.” At that very moment, Trane was dwelling on a screeching high note, and I wondered how Andrew, or anyone, could not get it? Why was the music I love so opaque to many people?

As an upperclassman, I began to organize and perform in regular monthly concerts on that same college campus, featuring top young jazz artists from New York: Ralph Moore, Kenny Garrett, Steve Nelson, and many others. First, the closet jazzophiles came out. They knew the artists and the music, and I was glad for their support. The audience ranked high in enthusiasm, if low in numbers. But then more and more students started to show up. They came out of curiosity, boredom, by happenstance, or because they wanted something to eat at the student center where these concerts took place. It didn’t matter why, just that they were there, and in numbers that shocked me.

Their initial curiosity soon became bona fide interest, and their interest began to translate into knowledge and familiarity and love. I started to run into some of these familiar faces at the local record stores, and they were buying Miles, Charlie Parker (“Bird”), Bill Evans, and Wynton Marsalis.

Now, well over a decade later, I see some of my newer friends and acquaintances going through the same process. They buy a few records, maybe read an article or see a movie like Round Midnight, and before you know it, they are hopelessly hooked.

It finally dawned on me. Jazz, even modern jazz, is not some arcane art form, reserved only for the cognoscenti. It can be accessible, even in its most abstract forms, and can speak instantly to and move listeners with the same force as any concerto or rock song. What jazz lacks is not inherent appeal but familiarity itself. People just have not heard as much jazz as they have Mozart or the Who. For whatever historical and perhaps racial reasons, jazz has never had the economic clout or mainstream support to become as ubiquitous as other music. While much of the typical music-loving public shies away from jazz because they think they don’t “understand” it–a refrain I hear often–classical or “legit” musicians sometimes dismiss jazz as a “popular” music unworthy of serious study. Neither impression is justified. Jazz is great music, plain and simple. When it becomes even slightly familiar to people, it invariably wins them over.

Jazz can be immensely complicated and brooding. As often as it can sound happy or sweet or shy, it also can be abstract, remote, churning, even upsetting. Much of my favorite jazz is anything but pretty, in the standard sense. But that breadth of emotional expressiveness is part of why jazz is such great music. With a little preliminary interest and willingness to listen, anyone can understand and respond to jazz. It involves different sounds and instruments, and is based on a principle of improvisation that makes it less predictable and accessible to some neophytes. And as is the case with twentieth-century painting, for instance, a little knowledge and understanding of how jazz works will greatly enhance your appreciation of the art form and make you want to hear more.

The purpose of this book is to familiarize you with some of the core ideas and elements of jazz, to help you become comfortable with the acoustic bass, lengthy tenor saxophone solos, and improvisations that can take you to a million unanticipated places. You will be introduced to some exemplary recordings that illustrate many of the elements of jazz as they have evolved historically. This book is not a primer on jazz history–of which there are many–although the historical development of jazz and improvisation is a necessary part of any discussion of how this music operates. Nor is this book the equivalent of a music appreciation class where you memorize what is recognizable in jazz’s twenty greatest hits.

What Jazz Is is an invitation to see how jazz works in simple terms and from the perspective of a working professional musician. You will get an insider’s look at how musicians choose their set list; the way musicians base their solos on song forms and interact with one another during improvisation; and the continuity that links Duke Ellington, Thelonious Monk, and Sonny Rollins to the current batch of young musicians.

Don’t get me wrong; jazz does not have to be an acquired taste. You can buy a jazz CD and become entranced right off the bat. I bought my first jazz record when I was nine years old, and I became a fan immediately. But if you take the time to learn the basics about jazz music and familiarize yourself with the players, you will enhance your listening experience immeasurably. Open your mind–and your ears–and begin the wonderful process of exploration.